Motivation

While many of functional programming concepts are derived from category theory, we often hear that it’s not necessary to learn it if we want to understand its concepts. This is, of course, is not true.

*But here's an article with a partially opposite opinion: https://jozefg.bitbucket.io/posts/2013-10-14-please-dont-learn-cat-theory.html

If Haskell is not a language of our choice, we are forced to map Haskell patterns to our language while these patterns are mapped to Haskell from category theory. A lot of important information is lost in translation.

This is why we start not from programming but from the theory itself. We will see that the theory is not only about programming but we will get back to some code samples at the end of the article.

When we formalize our ideas, our understanding is almost always clarified.

– David I. Spivak in Category Theory for Scientists

In fact, category theory is not so hard to grasp like we may think about. Some even think they can teach Quantum Mechanics in kindergarten with it. The theory is intended to make things simpler, by using the right “language” and formalism.

Things are getting more complicated if we map the theory implementation to the theory instead of mapping the theory to things we implement.

The purpose of this article is to write down very basic concepts of category Theory and only then get back to examples in the programming world.

Category Theory 101

Category Theory formalizes mathematical structure and its concepts in terms of a collection of objects and of arrows (also called morphisms).

– Wikipedia

Category theory is an area of mathematics that studies the properties of relationships between mathematical objects, which do not depend on the internal structure of these objects.

Objects and Morphisms

Let’s take an A and B. These are two objects, mathematical structures, types — whatever. No matter how do we call it because we don’t care about theirs internal structure.

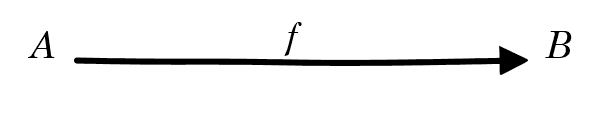

Now let’s draw a line between A and B and name it f:

This line is called morphism. While morphism isn’t necessary a function, in category theory, it usually means a function.

If we think about the morphism as about a function from A to B, we can also think about A and B as about types or sets:

f : A → B

Composition

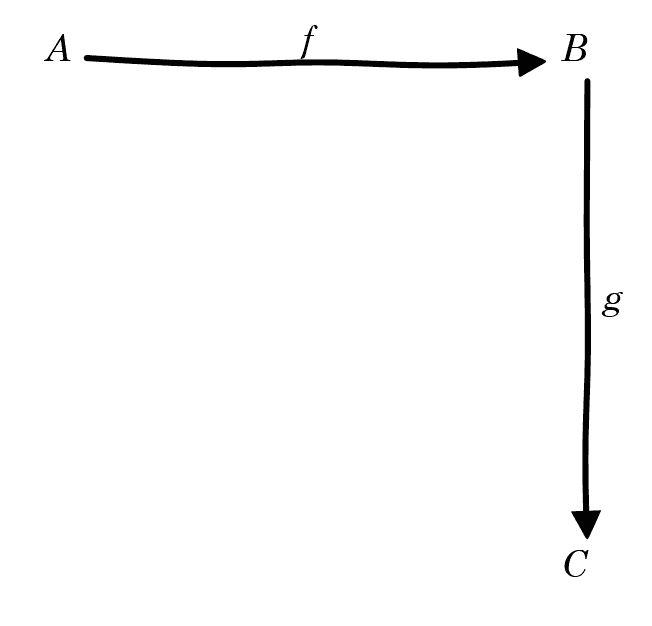

Now take another object, let’s call it C and let’s draw a g : B → C:

We can easily see that if we follow the arrows f and g we can get from A to C via B, because the end of f is the same as the beginning of g. Beginning of every morphism is called a domain (dom) and ending is a codomain (cod). So we can say that:

A = dom(f), B = cod(f)

and for f : A → B and g : B → C:

cod(f) = dom(g)

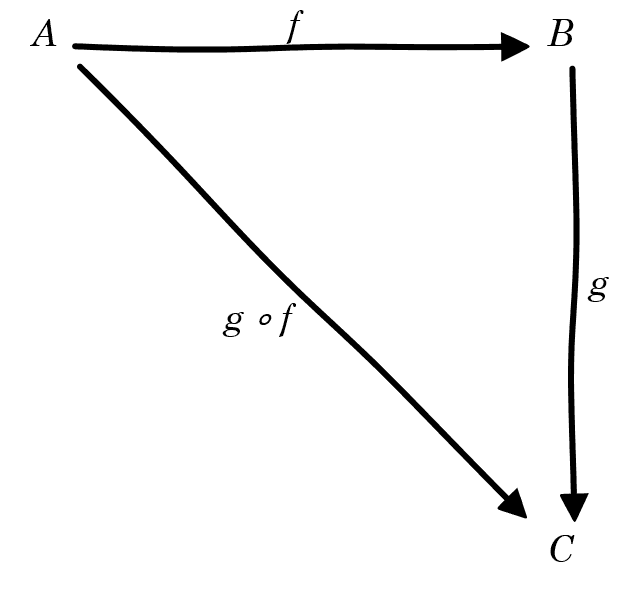

Joining two morphisms that match with their domain and codomain is called composition and denoted as:

g ∘ f

which produces a new morphism (function). So that:

∀ a ∈ A, (g ∘ f)(a) = g(f(a))

which means: for every a in A, a composition of g after f applied to a is the same as the result of g(f(a)).

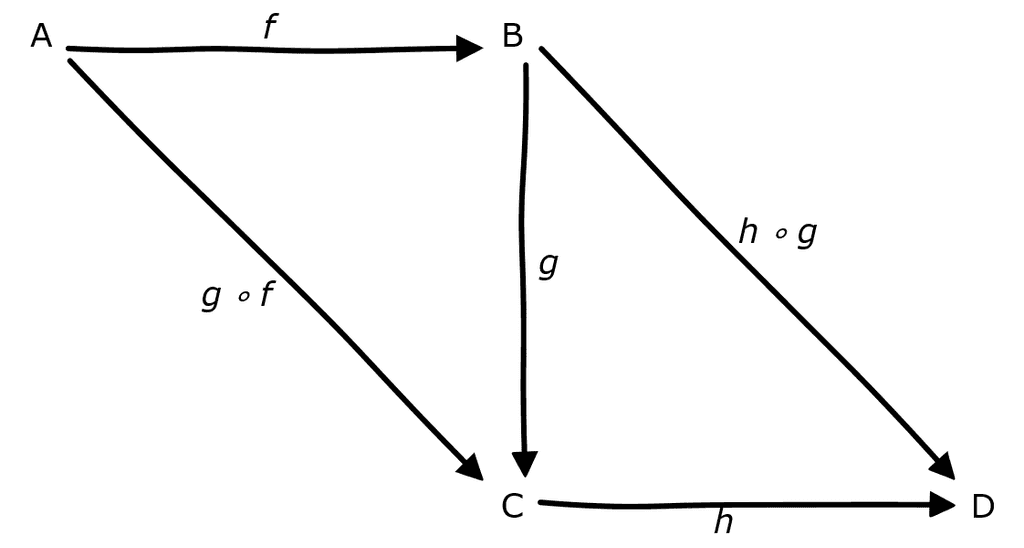

In this way, we can connect as many objects as we need. For example:

h : C → D

Associativity

Operator ∘ is associative:

(h ∘ g) ∘ f = h ∘ (g ∘ f)

∵ ∀ a ∈ A, ((h ∘ g) ∘ f)(a) = h(g(f(a)))=(h ∘ (g ∘ f))(a)

Identity

Every object we introduced has an Identity morphism:

1A : A → A

∀ a ∈ A, 1A(a) = a

Identities are composable as usuall morphisms:

f ∘ 1A = f = 1B ∘ f

Category

Now we have everything to define a category.

A category consists of following:

- Objects:

A,B,C, … - Morphisms:

f,g, … - Identities for every object:

1A,1B,1C, …

The following laws must be satisfied:

- Associativity:

(∀ f : A → B, g : B → C, h : C → D), h ∘ (g ∘ f) = (h ∘ g) ∘ f

Which means: for all the functions that are composable with each other composition is associative.

- Unit:

(∀ f : A → B), f ∘ 1A = f = 1B ∘ f

Which means: every function f : A → B is equal to f ∘ 1A and is equal to 1B ∘ f.

So generally speaking, a category is a set of objects connected with arrows and limited by associativity and unit laws.

Of course, there is a lot more interesting in category theory, but these basics are enough to start thinking about more complex concepts. All these monoids, functors, monads etc. are just about connecting objects with arrows and this is not only about programming.

Get into the code

It’s natural to map these concepts to any of modern programming languages.

Haskell

f :: Integral a => a -> Bool

f a = mod a 2 == 0

g :: Bool -> [Char]

g b = if b then "True" else "False"

composed :: Integral a => a -> [Char]

composed = g . f

composed 2 -- True

composed 3 -- False

JavaScript:

const compose = (g, f) => a => g(f(a))

const f = a => a % 2 == 0

const g = b => (b ? "True" : "False")

const composed = compose(g, f)

console.assert(composed(2) === "True")

console.assert(composed(3) === "False")

C#:

using System;

using Xunit;

namespace Category

{

public static class CategoryExtensions

{

public static Func<A, C> Compose<A, B, C>(this Func<B, C> g, Func<A, B> f)

{

return x => g(f(x));

}

}

public class CategoryTest

{

Func<int, bool> f = (int i) => i % 2 == 0;

Func<bool, string> g = (bool b) => b ? "True" : "False";

[Theory]

[InlineData(2, "True")]

[InlineData(3, "False")]

public void Composition(int input, string output)

{

// Act

Func<int, string> composed = g.Compose(f);

// Assert

Assert.Equal(composed(input), output);

}

}

}

F#:

// val f : (int -> bool)

let f a = a % 2 = 0

// val g : (bool -> string)

let g b = if b then "True" else "False"

// val composed : (int -> string)

let composed = g << f

> let x = composed 2 ;;

// val e : string = "True"

> let y = composed 2 ;;

// val y : string = "False"