Everyone who learned Danish knows that there are two grammatical genders in the language: common (or n-words) and neuter (or t-words).

According to Wikipedia:

Historically, nouns in Danish and Swedish, like other Germanic languages, had one of three grammatical genders: masculine, feminine, or neuter. Over time the feminine and masculine genders merged into a common gender.

Most of the Danish nouns are n-words and there are no rules about how to distinguish between n- and t-words. Teachers usually recommend just to remember.

On the other hand, people usually say about a new word they hear that it sounds like n- or t-word.

If one says that a word sounds like a t-word, could it be that our intuition is able to build up some rules to solve this question? I was always interested to find an answer to that question.

The simplest thing I could do is to ask a computer to classify the Danish nouns and find the rules to distinguish between n- and -t.

I took an XML-file with Danish a big set of Danish words from the Wiktionary dumps (thanks to Steve for pointing me there) and applied an R-script to process and classify the data.

library(xml2)

xml <- read_xml("./data/dawiktionary-latest-pages-meta-current.xml")

nouns <- data.frame(

xml_text(xml_find_all(xml, "//d1:page//d1:title", xml_ns(xml))),

xml_text(xml_find_all(xml, "//d1:page//d1:text", xml_ns(xml))))

colnames(nouns) <- c("title", "text")

This gives us a data frame with 48008 rows, let’s remove everything but nouns from the data frame:

nouns <- nouns[!grepl(":", nouns$title), ]

nouns <- nouns[grepl("\\{\\{-noun-\\|da\\}\\}", nouns$text), ]

nrow(nouns) # 8004

Now we have 8004 nouns, let’s add a column et, it should contain boolean values: et for t-words and en for n-words:

nouns$et <- apply(nouns, 1, function(x) {

ifelse(

grepl(paste("et\\|", x[1], sep = ""), x[2], ignore.case = TRUE),

"et",

"en")

})

nouns$et <- factor(nouns$et)

nouns$text <- NULL

nrow(nouns[nouns$et == "et",]) # 1552

nrow(nouns[nouns$et != "et",]) # 6452

Next step, add more columns with attributes in order to let computer classify the words by these attributes. Let’s start with word’s length and build a decision tree based on this attribute:

library(party)

nouns$letters_count <- apply(nouns, 1, function(x) nchar(x[1]))

tree <- ctree(et ~ letters_count, data = nouns)

plot(tree)

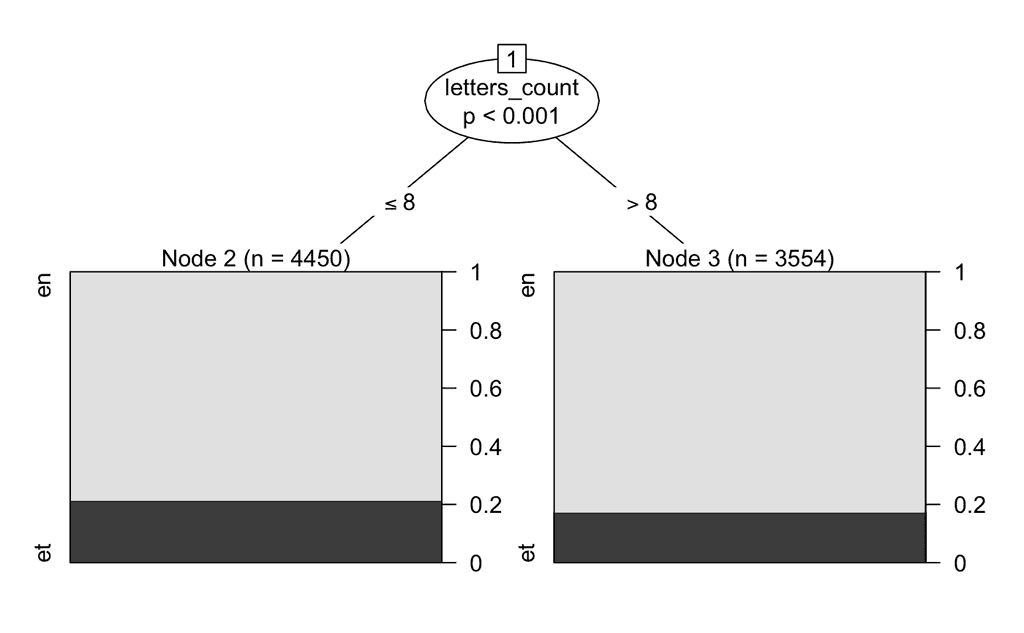

As we can see from the plot, there are slightly less than 20% of t-words between the words, which length is more than 8 symbols and there are slightly more than 20% of the words, which length is less or equal than 8 symbols. So far this doesn’t look like an effective set of rules as the part of t-words in our data frame is about 19%. But let’s write a function which will apply our set of nouns to the decision tree and will count how many times the decision tree will give us a right answer about is it a n- or t-word:

test_tree <- function(tree, nouns) {

prediction <- data.frame(nouns$et, predict(tree, nouns))

colnames(prediction) <- c("fact", "prediction")

prediction$valid <- apply(prediction, 1, function(x) ifelse(x[1] == x[2], TRUE, FALSE))

nrow(prediction[prediction$valid,])

}

test_tree(tree, nouns) # 6452

There are 6452 right answers which coincide with a number of n-words in the nouns data frame. Therefore, our decision tree is not so effective.

What if noun’s gender correlates with first of last letters the word? Let’s add more attributes to check this. There are 29 letters in the Danish alphabet, so there will be at least 29 boolean attributes for every first letter, at least 29 for every last letter. By the same principle, let’s add attributes for first two and last two letters of every word (29 * 29 = 841).

# Dansk ABC

abc <- c(

"A", "B", "C", "D", "E", "F", "G", "H", "I", "J",

"K", "L", "M", "N", "O", "P", "Q", "R", "S", "T",

"U", "V", "W", "X", "Y", "Z", "Æ", "Ø", "Å")

columns <- c("letters_count")

for (letter1 in abc) {

letter <- letter1

column_name <- paste("first_letter_is_", letter, sep="")

column <- apply(nouns, 1, function(row) ifelse(toupper(substring(row[1], 1, 1)) == letter, TRUE, FALSE))

if (length(column[column==TRUE]) > 0) {

nouns[column_name] <- column

columns <- append(columns, column_name)

for (letter2 in abc) {

letter <- paste(letter1, letter2, sep="")

column_name <- paste("first_letter_is_", letter, sep="")

column <- apply(

nouns, 1, function(row) ifelse(

toupper(substring(row[1], 1, 2)) == letter,

TRUE, FALSE))

if (length(column[column==TRUE]) > 0) {

nouns[column_name] <- column

columns <- append(columns, column_name)

}

}

}

}

for (letter1 in abc) {

letter <- letter1

column_name <- paste("last_letter_is_", letter, sep="")

column <- apply(

nouns, 1, function(row) ifelse(

toupper(substring(row[1], nchar(row[1]), nchar(row[1]))) == letter1,

TRUE, FALSE))

if (length(column[column==TRUE]) > 0) {

nouns[column_name] <- column

columns <- append(columns, column_name)

for (letter2 in abc) {

letter <- paste(letter2, letter1, sep="")

column_name <- paste("last_letters_are_", letter, sep="")

column <- apply(

nouns, 1, function(row) ifelse(

toupper(substring(row[1], nchar(row[1]) - 1, nchar(row[1]))) == letter,

TRUE, FALSE))

if (length(column[column==TRUE]) > 0) {

nouns[column_name] <- column

columns <- append(columns, column_name)

}

}

}

}

tree <- ctree(as.formula(paste("et ~ ", paste(columns, collapse = "+"))), data = nouns)

plot(tree)

test_tree(tree, nouns) # 6595

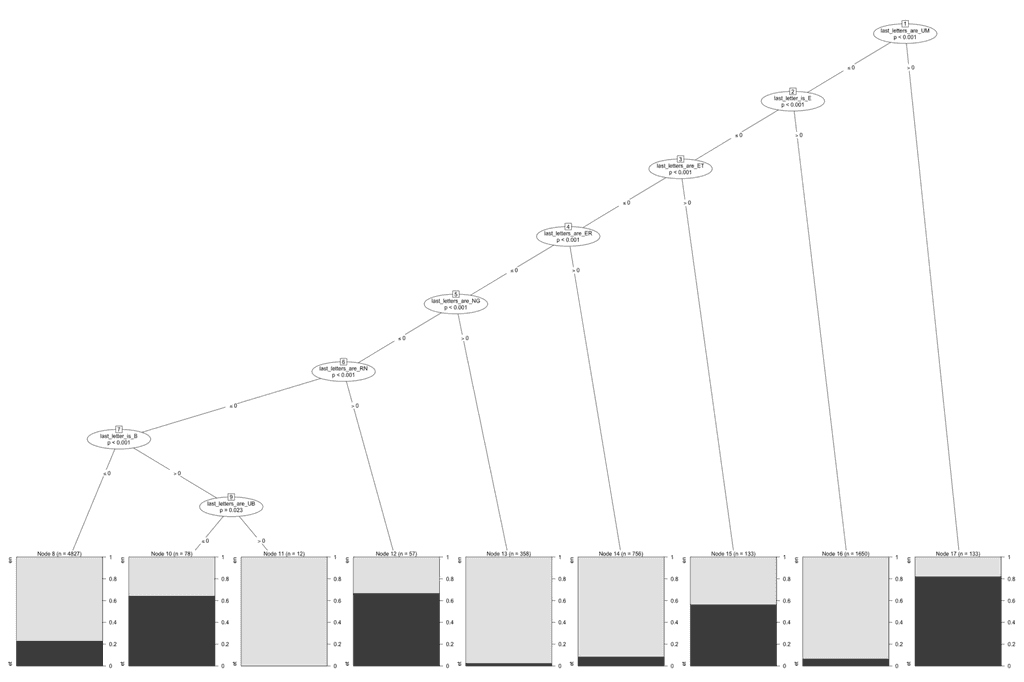

This tree gives us 6595 right answers, which is only 143 answers more, but still not enough to rely on it. For the other hand, we can see that there are some signs that we can use and maybe our brain uses when we feel that some word sounds like n- or t-.

For example:

- Out of 133 words ending by “um”, there are 109 t-words (82%). For example: et amfibium, et faktotum, et punktum, but en rosarium.

- Out of 1650 words ending by “e”, there are only 110 t-words (7%). For example: en næse, en pige, but et æble.

Conclusion: unfortunately, it’s easier to remember all these words. Even if there are some rules that let us guess the right grammatical gender, they are more complex than just a set of first and last letters.