This page is a mental experiment I have made over a weekend. I am not pretending to be an expert in quantum physics, and my interpretation is most probably not precise.

Nevertheless, it may help to build an intuition about these things.

Let's imagine a world where 2-dimensional particles exist. Each particle is a vector that points to a random direction from 0 up to 2π radians (i.e., from 0˚ up to 360˚).

Each particle has only one property - angle, but according to this world's rules, the inhabitants can't measure a particle's angle directly - they can only use two-dimensional detectors.

A detector is nothing more than another vector that an inhabitant can rotate to any angle. We provide the inhabitants a detect function that accepts a detector and a particle and returns either +1 or -1.

Here is an example of a very classical detect function. It will return one (+1) if the angle between the particle and the detector is less than 90˚. In other words if the cosine of this angle is greater than zero (0). Otherwise, the function will return minus one (-1).

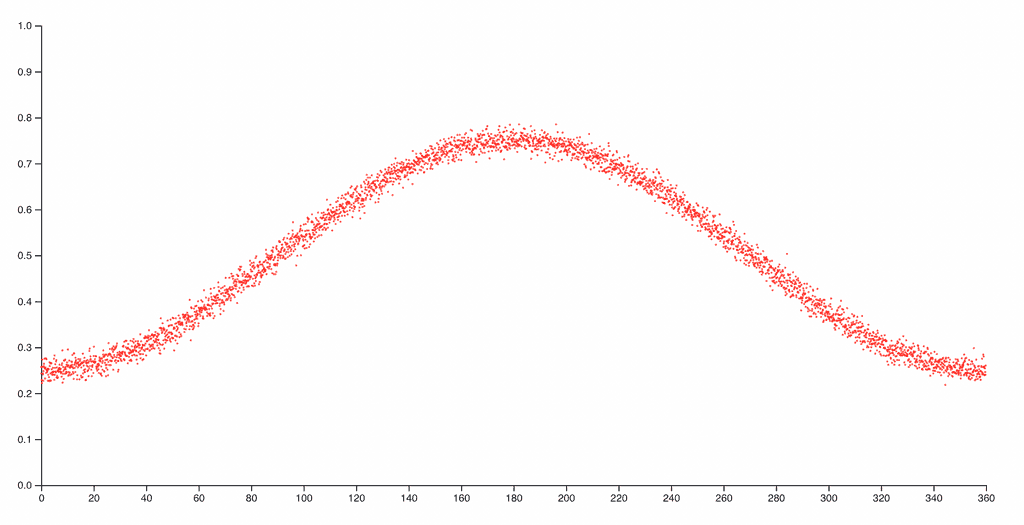

Now, let's experiment: for each angle from 0˚ to 360˚, let's take two detectors that have this angle between each other. Then, let's prepare two particles, which angles are random except that each particle's angle is always opposite to another. Let's do this experiment, say, 1000 times per each angle from 0˚ to 360˚, and chart how many times our detectors will return the same results:

We shall not be surprised by what we see. Indeed, if one particle is 0˚, then another (the opposite) must be 180˚. If our detectors are in the same direction (0˚ between each other), they always show the opposite results. If the detectors are 180˚ to each other, they both show the same results. The rest of the cases falls between these two.

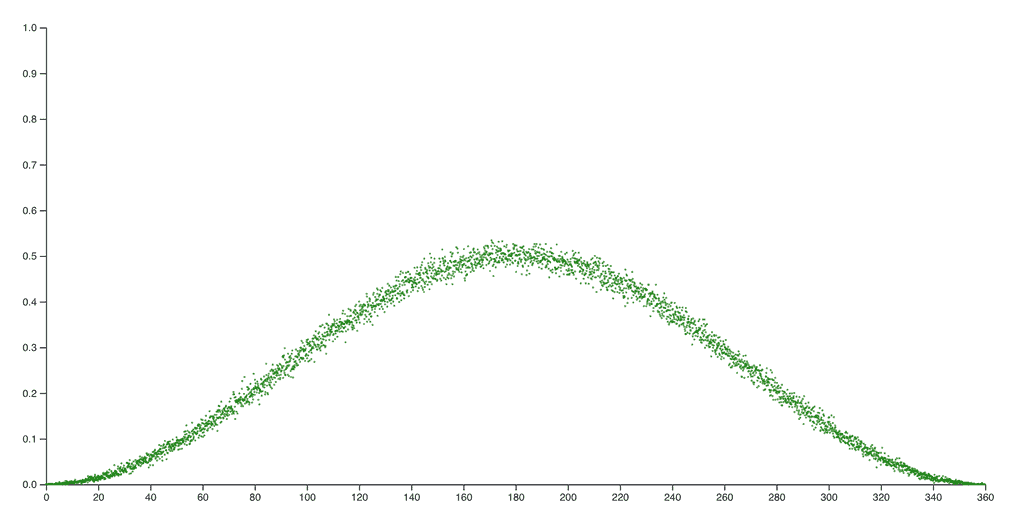

A significantly different situation would be if we did the same experiment with a semi-quantum detect function. It will not deterministically return +1 or -1, but instead, it will return either +1 or -1 with a probability of cosine of the angle between the two detectors:

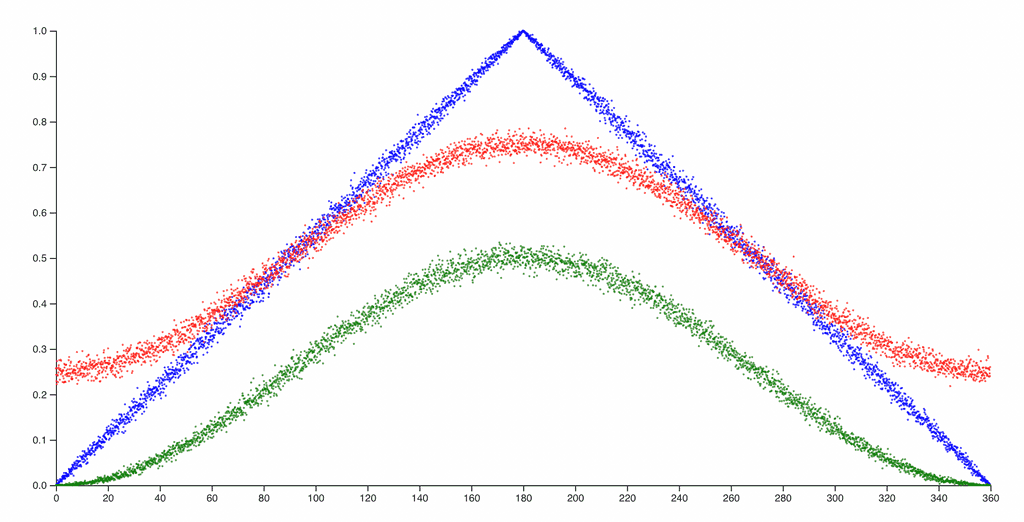

Now, the picture is very different. But here, we still have two deterministic particles that are not connected when they are detected. What John Bell proves in his theorem is that a pair of entangled particles is detected like these particles are connected even if they are far away from each other. To emulate this, we introduce a quantum detect function. It does not only return -1 or +1 with a probability of cosine between the particle and the detector, but it changes the particle's angle to the detector's angle if the result is +1 or to the opposite angle if the result is -1.

We will emulate the entanglement by measuring the same particle and inverting the results of the second detector:

Let's plot all three detect functions on the same chart to see the difference:

Please, fork this notebook and fix it if you see that my explanation is not precise or is entirely wrong.

Thank you!